Why You Can’t Just “Blow Tone”

Have you been told to blow tone or blow steady? Does your chanter reed cut out or squeal? Is it hard for you to tune your drones to your chanter? Does this whole concept of great tone seem ambiguous?

In this recording, Andrew defines tonal quality and explains how to get it in simple, easy to follow steps. Imagine not just blowing tone but actually producing great tonal quality on your bagpipes!

Video Transcription:

What's tonal quality mean? It equals the sound your instrument produces. Yeah, I liked that. Tonal quality equals how about the quality of the sound your instrument produces?

It's really easy to get a bagpipe to make sound. It's very difficult, relatively speaking, to get it to produce a good sound. Now a lot of that has to do with tuning, but what tonal quality refers to does not include tuning. Here's our bagpipe tree of sound everyone. Isn't it exciting. The bottom layer here, sometimes known as what? Maintenance. Up here at the top of the tree tuning. Right, tuning is what we ultimately need to be able to do. But then there's this important middle step and that's what we're talking about today, which is tonal quality. Tone or tonal quality.

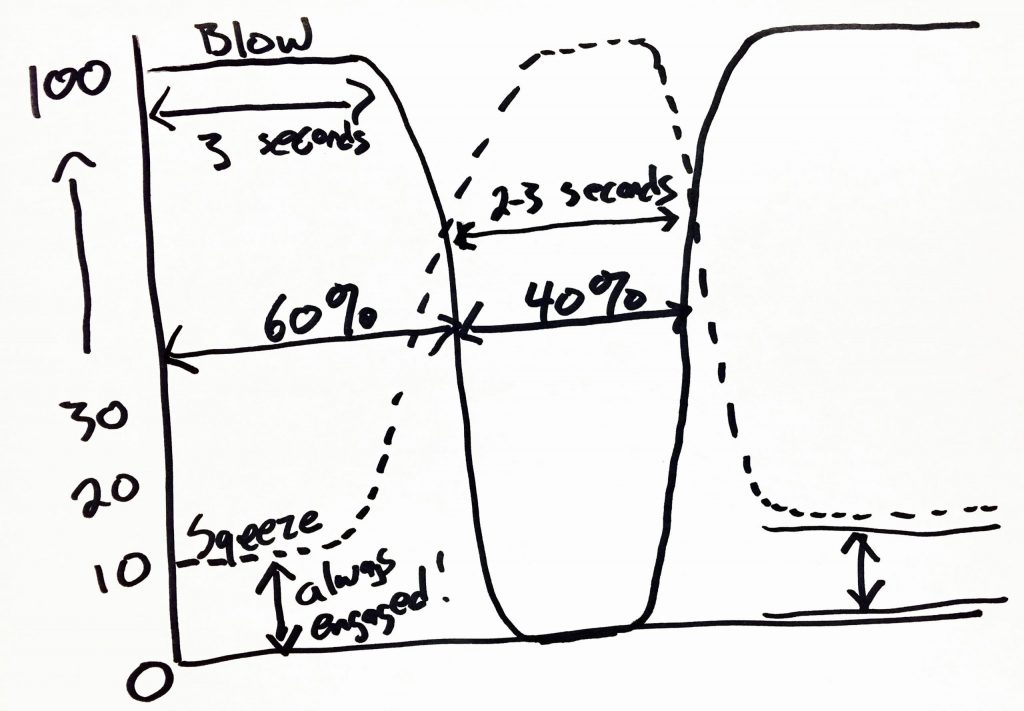

And the idea is there are different levels. There are different qualities of tonal quality we can get out of the instrument. What does Andrew mean by that? So for starters, let's take our chanter reed, right? This, the following diagram is meant to represent the range of possible pressures you could blow your bagpipes at. Down here this bottom one is the point where your chanter reed begins to make a sound. What do we sometimes know? Like what do we call this line in dojo speak? This is the line where you chanter reed. Everybody knows it, right? It's when you start to blow and you get the hissy air sounds, and then all of a sudden that a certain pressure, the reed starts to make us out, the point where that chanter reed kicks in. All right? Now we call this the choke line.

Because the same is true the other way, right? If our reed is making a sound, but then suddenly it dips below this point, the sound cuts out and we get what's called a choke. Pretty easy stuff, but you'll see why it's about to become really important.

My practice chanter reed has the same line. So if I just blow into this, nothing is, no sound is coming out of the reed until I reach a certain pressure. And then it starts to, it starts to kick in. Right?

Now when the sound starts to kick in, is it a good quality of sound or not? And think about your own bagpipes here. And I could, I can grab a chanter here. This sort of thing tends to get pretty distorted. So you know, you just kind of have to use your imagination, right? But when the sound first starts to kick in, so here's my reed. Notice how if I don't blow hard enough, no sound comes out of the reed. We all know this. Okay. But once I get to a certain pressure, the sound will kick in, right? And it's, it's amazing on a, on a bagpipe chanter reed, it comes in all of a sudden, out of nowhere. It goes from no sound to sound. It's quite remarkable, right? But then when the sound comes in, if we were to start to play a tune, like really close to that choke line, the sound of the timbre is not good.

You might not be able to tell, cause I'm sure it's very distorted. Because it's very loud, right? The sound is not good down at that choke line, right? But what I really want you to understand about that is we've all heard bagpipe chanters that sound good, but it doesn't sound good there.

So that really kind of shows that we have a range of possible pressures we can play on our chanter, right? It's not just blow in it until it makes a sound and then we're good. Does everybody understand? There's a range of possible pressures we could play on the chanter. It's not just one pressure. It's not just a thing we blow in, we hear the sound, and then we're off to the races. That was maybe true the very first day we stuck a chanter in our pipes. Like, Hey, congratulations, you got a few notes out. Right? But you know, basically by day two we have to realize there's a range of possible pressures.

And the other thing that what I just did would kind of expose, if I blow harder on my reed, okay, the sound starts to get what?

Right. If I blow harder on my read, all of that scratchy, awful sound starts to go away and it starts to sound nice. The harder we blow on our chanter, the better the sound gets. Principle number one. Sure, I guess we'll call it a principle. The harder we blow on our chanter reed, the better it's going to sound.

Let's pretend I'm a regularly blowing around here. If I blow a little bit harder, I'll have a little bit more harmonics, a little bit more richness, a little bit better quality of sound, but I could go a little more and I get a little bit better harmonics, a little bit better quality of sound, so on and so forth. I don't know. I've never measured it. Maybe it's even slightly louder because of all these added harmonics. I'm not sure. A little bit better sound. So the harder I blow, the better it sounds.

And then John says, until you blow too hard. What does that mean? There's a point where if we blow any harder, our reed starts to behave unpredictably. Right? This area up here, there's a point where it starts to, I mean, I'm sorry I covered over the definition of tonal quality there, but there's a point where we can't blow any harder or else the reed starts to get overloaded and make unpredictable sounds. These sounds could be as severe as a squeak. Right? Or that could be as minor as just a sort of like strange distortion sound.

Regardless, it's something we can't really control and it's something that definitely doesn't really sound as intended. We're getting something more than just a C. We're getting a C plus some bizarre overtones that are caused by blowing too hard on our instrument. So that is what the top end of the range represents. This is like, this is the control line. I mean, I don't know what we call it. We have a, we have a thing for the choke line here and we do have a name that we call it, but this is a, this is the controllable line or this is the distortion line. At any point above that line, things start to get distorted, okay? Now there's another thing that we call this line.

All right? This line has another much better fun name, which is? Everybody knows it as the sweet spot. So when we blow our bagpipes, we want to blow exactly at this line, all right? Now some of you might say, Andrew, you are a crazy extremist and I would never want to blow exactly at this line because anywhere above that line, and I'm in the land of distortion. I'm in the land of uncontrollable sounds, but let me ask you this, right? If I blow even a, you know, even a half of an inch down, right? If I blow even half an inch down, wouldn't that sound better if I moved it up? Based on the principle that the harder I blow, the better my chanter reed sounds? Yes, it would. It would sound better if I did that. So let's move a little bit closer, but still not all the way to the line, right, because we don't want to go to the line cause that's scary.

But now I moved even closer. Let me ask you the same question. If I blew just a little bit harder, wouldn't it sound just a little bit better? Yes, it would. All right. Now let me ask you, let me ask you the next question. If I accidentally blowed just a little bit beyond that sweet spot distortion line, what happens? Is it pure catastrophe? If I blow just a little bit above that line? No, your drone reeds don't cut off if you've calibrated them properly. Now I liked that Aric said not unless you're on low G playing a bunch of G grace notes. And if you are playing a bunch of G grace notes and you just ever so slightly above the line, it's not like you get a catastrophic super honk, right? You would just get a very slight distortion. So the risks of going beyond the distortion line are not that high.

As long as you're not way above. Right. And then meanwhile, anytime you drop below that line, you're sacrificing quality of tone.

So the objective at all times is to do what? So my objective at all times is to blow at the sweet spot. If I am blowing at the sweet spot at all times. Think about that at all times. And if I succeed to blow out the sweet spot at all times, what does that also mean if I'm succeeding at blowing at the sweet spot at all times? John Holcomb is reading my mind a little bit. If you're at the sweet spot at all times, that means there's never a time that you're not exactly at that line, which means blowing steadily.

My point, so my point here is most people assume tone or tonal quality is just about blowing steady, but it's actually not even a top priority of mine. Certainly not as a teacher, right? Because what I really want to do is get people to hit that sweet spot and never leave. If, if we can succeed in finding the sweet spot and then never leaving, we're already blowing steadily. We have a couple of articles where the title is along the lines of forget blowing steady. We do need to blow steady and actually blowing steady is a very tricky thing to do, but make your top priority hitting the sweet spot and let you know a bulk of steady blowing development happened just naturally as a bonus of hitting that sweet spot regularly.

Enjoying this content and want to try Dojo U? Try our Premium Membership for a full month for just one dollar by clicking here now!Try a Dojo U Premium Membership for $1

Responses